Planet-scale environments with PCG

In Subsolar, we’re building full-scale, playable planets. We use heightmaps and geologic data from NASA to shape our environments. The goal is to make our environments as realistic, aesthetically pleasing, and as performant as possible. There can be significant technical problems when dealing with full-scale planets. The project has to contend with gravitational logic, optimization, and headache-inducing floating point precision issues, for example. One of the big challenges the environment team has is making a fully-playable planetary surface look as varied and diverse as the planets we seek to recreate.

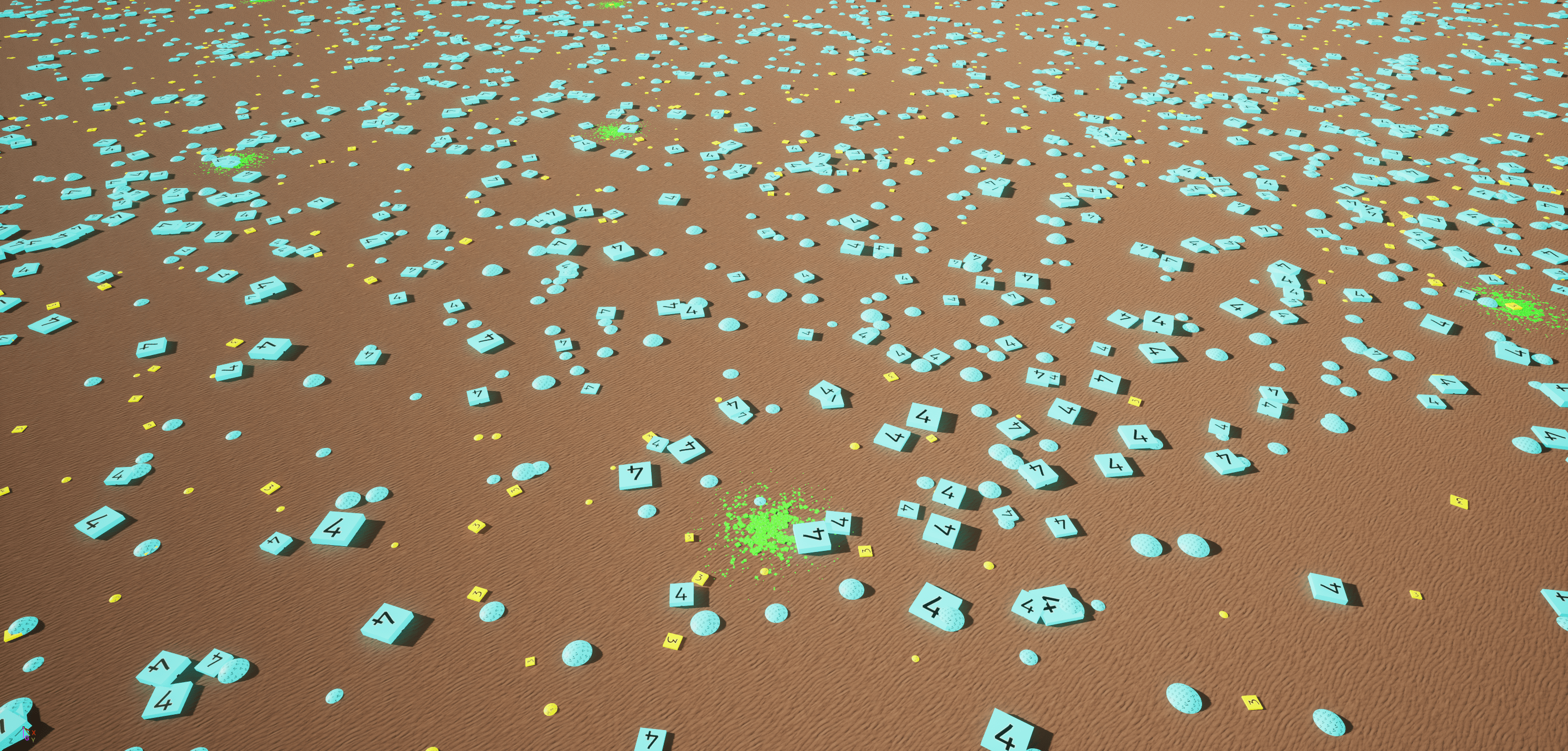

Our working solution for creating biome-by-biome variance is leveraging the use of data assets in Unreal Engine’s Procedural Content Generation framework (PCG). This is a workflow that allows us to quickly generate varying distributions of meshes and other actors. It’s essentially a ‘foliage system’ we’ve assembled for flexible and modular implementation. Since we’re building planet simulations for Mars, Venus, and the moon, however (i.e. no true “foliage” to speak of), this typically involves spawning different varieties of rocks, cliffs, dust, debris, and weather based on the geologic biome we’re in. On our Mars level, these biomes are currently roughly grouped by Plains, Volcanic, Rough, Canyon, and Polar terrain. In the future, we intend to use these tools in a hierarchical way to create even more variance within these larger-scale regions.

Note: For reasons we won’t address in-depth here, the native experimental PCG biome tool doesn’t quite work well with or fit the needs of our project, partially due to our in-house planet rendering pipeline.

Pipeline Overview #

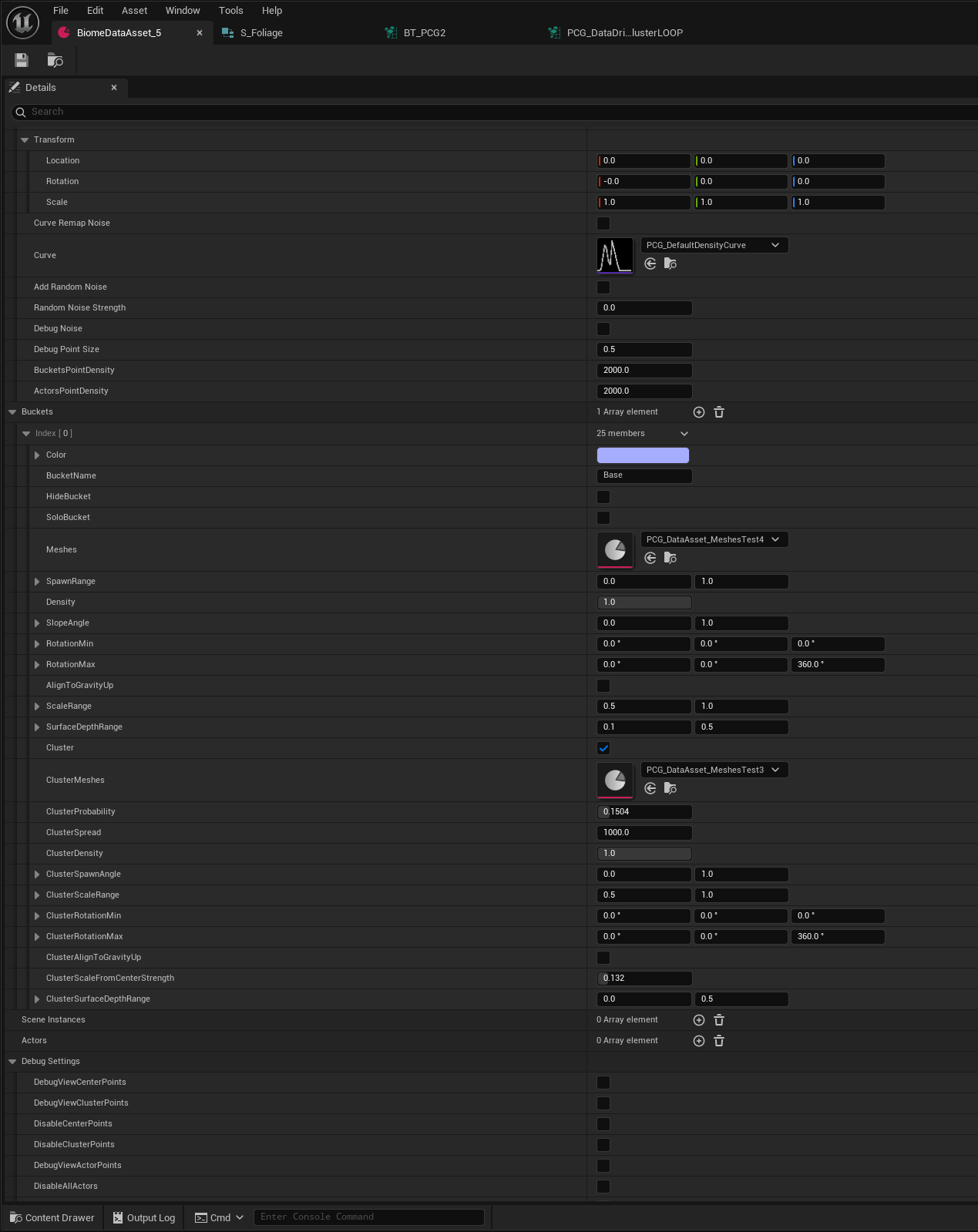

The way our pipeline works is by first establishing a structure for our data assets. We populate these data assets with modular content (per-biome), such as rocks, cliffs, and weather effects. This data then gets passed off to a master PCG graph (and its subgraphs/loops) which handle point generation, instancing, and distribution based on the data it’s given.

The utility of using a master graph is that we can quickly and effectively generate variance through sets of data. This is preferable to hand-crafting a multitude of PCG graphs with very similar behavior, which would essentially entail manually re-crafting recurring node chains and parameters. By consolidating things into a master graph, creating clusters is done with the click of a button. Adding new sets of rocks and cliffs for a new region only involves dragging them into place and adjusting a few parameters.

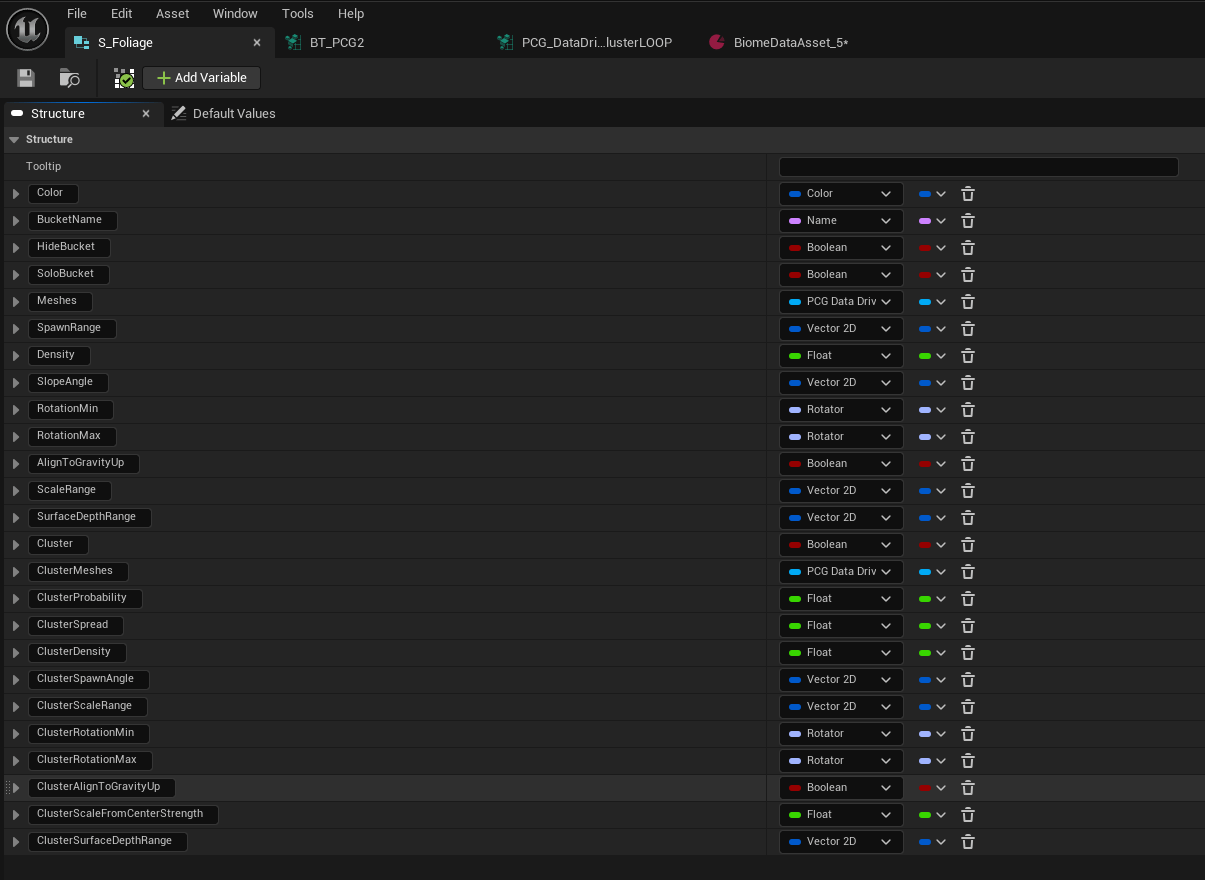

The Data Structure #

First, we made a structure for all of the parameters our data assets would need to handle. Initially this was just a few fields to prove out the methodology—passing basic data like scale, rotation, and density per mesh. Piece-by-piece, we’ve built it out into a comprehensive and encompassing system.

Then we created the data assets themselves (which use this structure). Here, we pass in varying meshes and other actors, adding them to an array of “buckets.” A typical start for our biomes is assigning a number of rock meshes of varying sizes to each of these buckets. From here, we can dial their distribution, scale, rotation, density, cluster probability, and various other parameters.

The data structure can not only spawn rocks—but cliffs, debris, fog, level instances, and various other actors. We can even spawn procedural weather effects by bundling Niagara components and spatial audio components into basic blueprint actors, effectively placing dust storm VFX and SFX through PCG.

The PCG Loop #

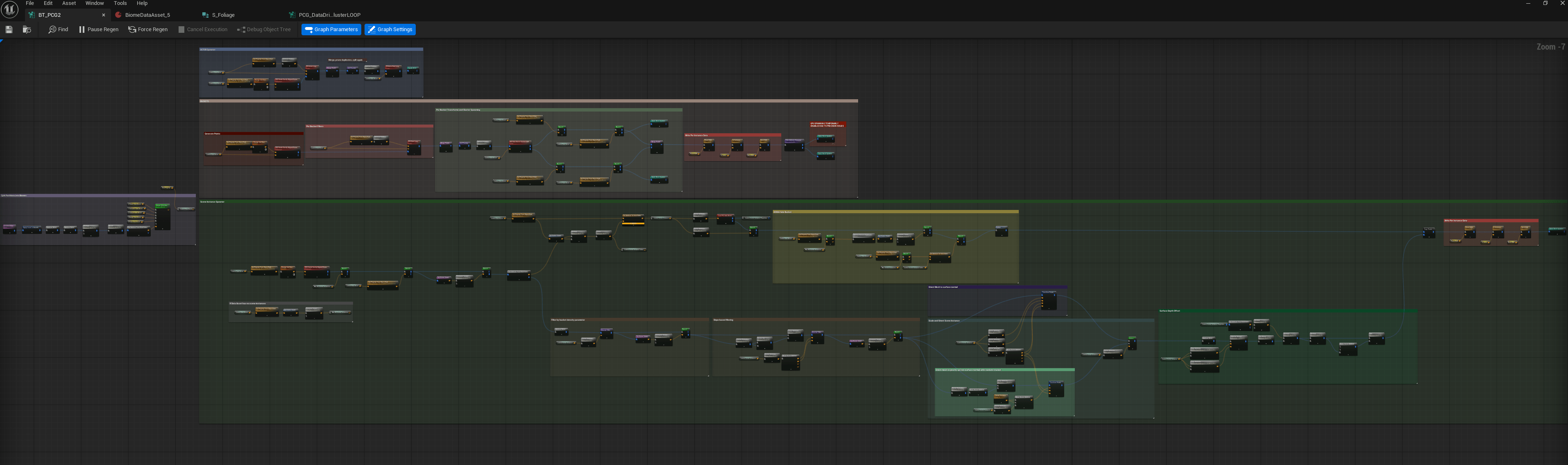

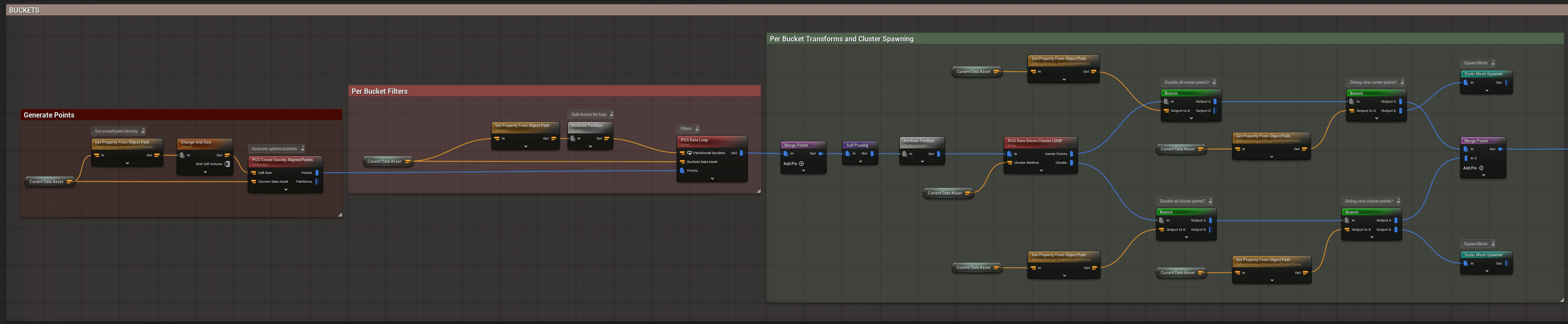

Once we have our data assets set up, we pass them into our master PCG graph. Our master graph takes that data and assigns a biome, aligns the PCG partition’s ray query gravitationally, generates points, passes the data through its loops, and spits out our rocks and other actors via static mesh spawners (or other appropriate spawners).

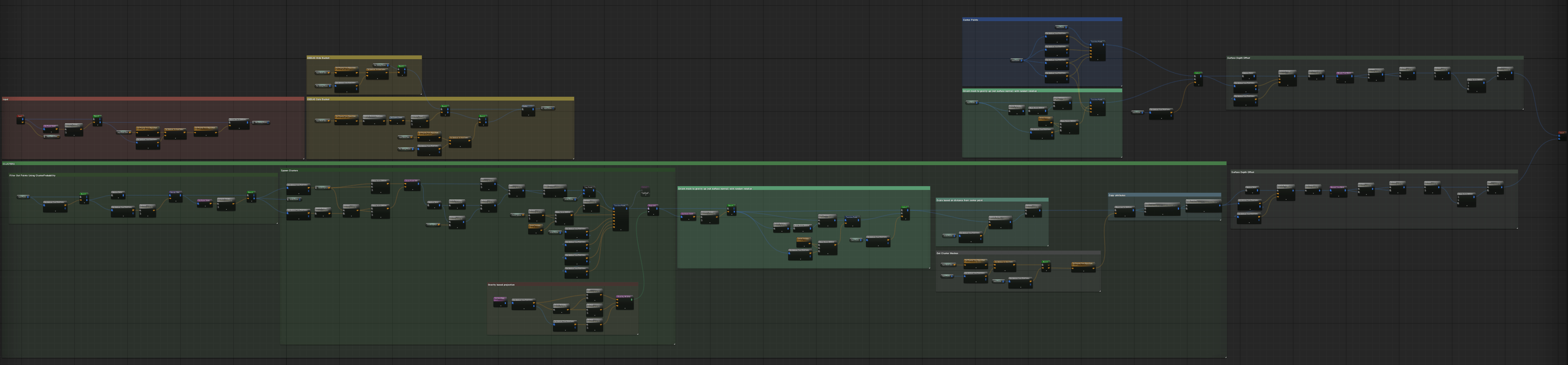

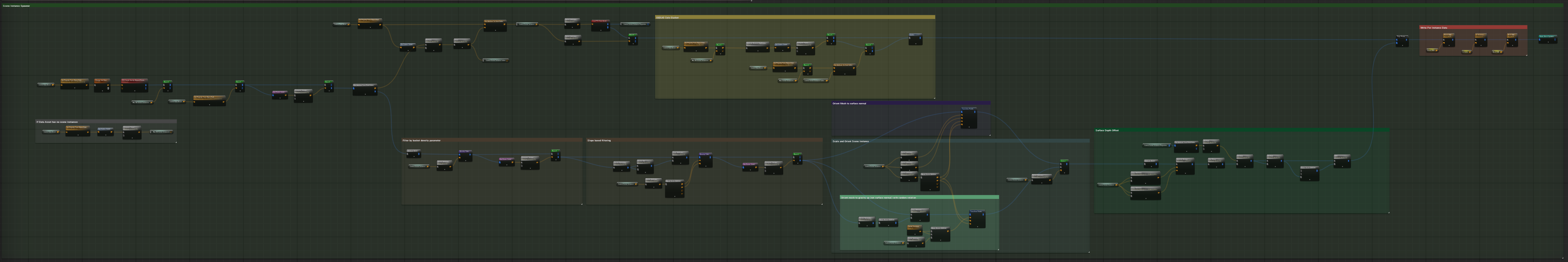

Here’s our master graph, which consists of a few subgraph loops as well.

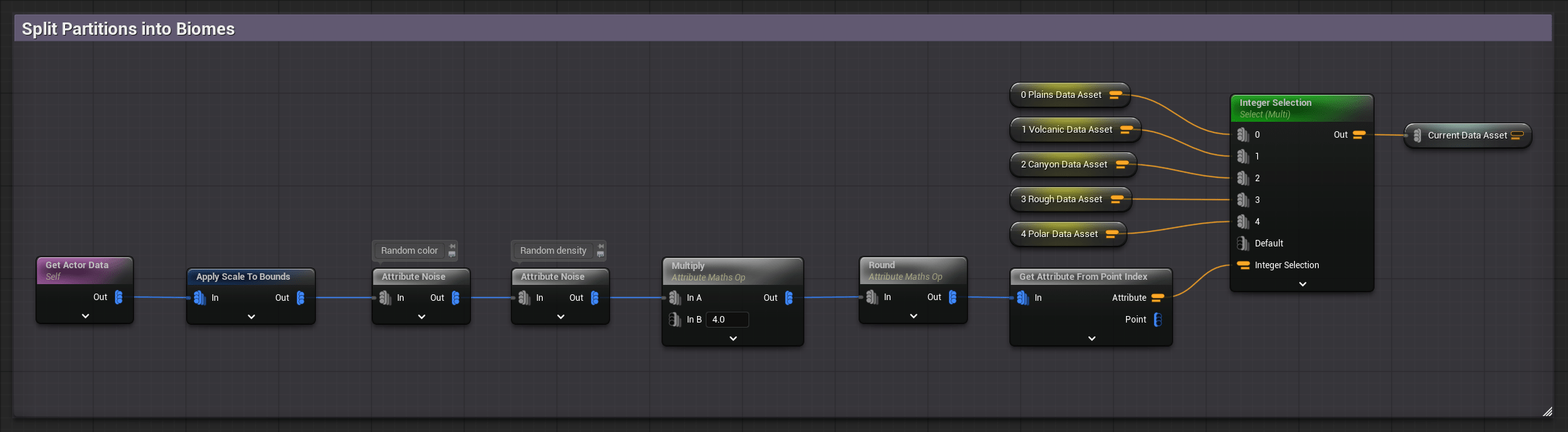

Biome selection and corresponding data assets get selected at the beginning of the graph.

We then generate points and align them gravitationally. These points get split per bucket, as is set in the data asset. Each bucket might contain something like an array of small rocks or cliffs, for example. Each data asset might contain varying arrays of rocks of different sizes, cliffs, weather effects, etc. We then assign meshes to each point (in our Data Loop) and spawn clusters (in our Cluster Loop).

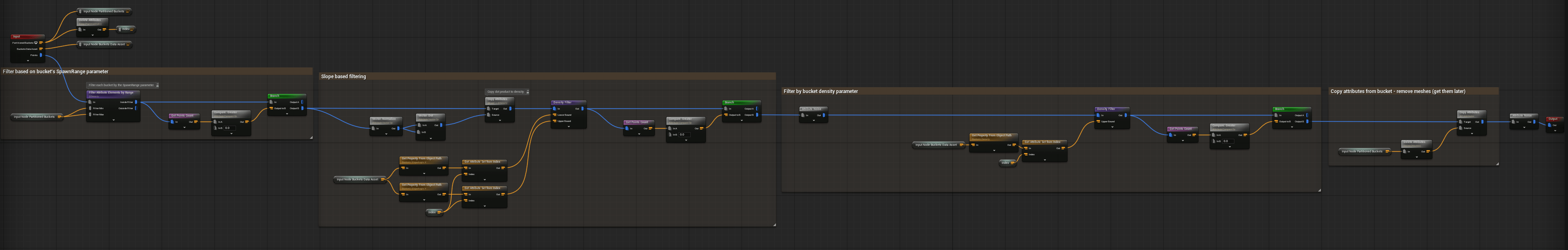

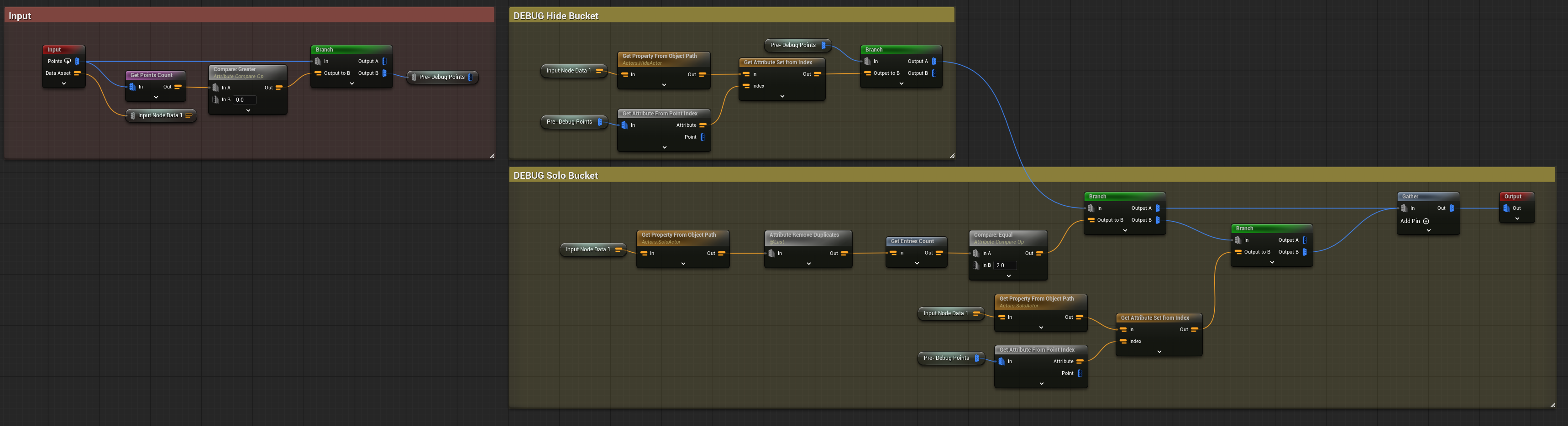

The interior of the graph contains both our Data Loop and Cluster Loop. These are basically nested nodes responsible for putting data into action when it comes to density, distribution, slope, and other sorts of filtering. Here’s a look inside those loops:

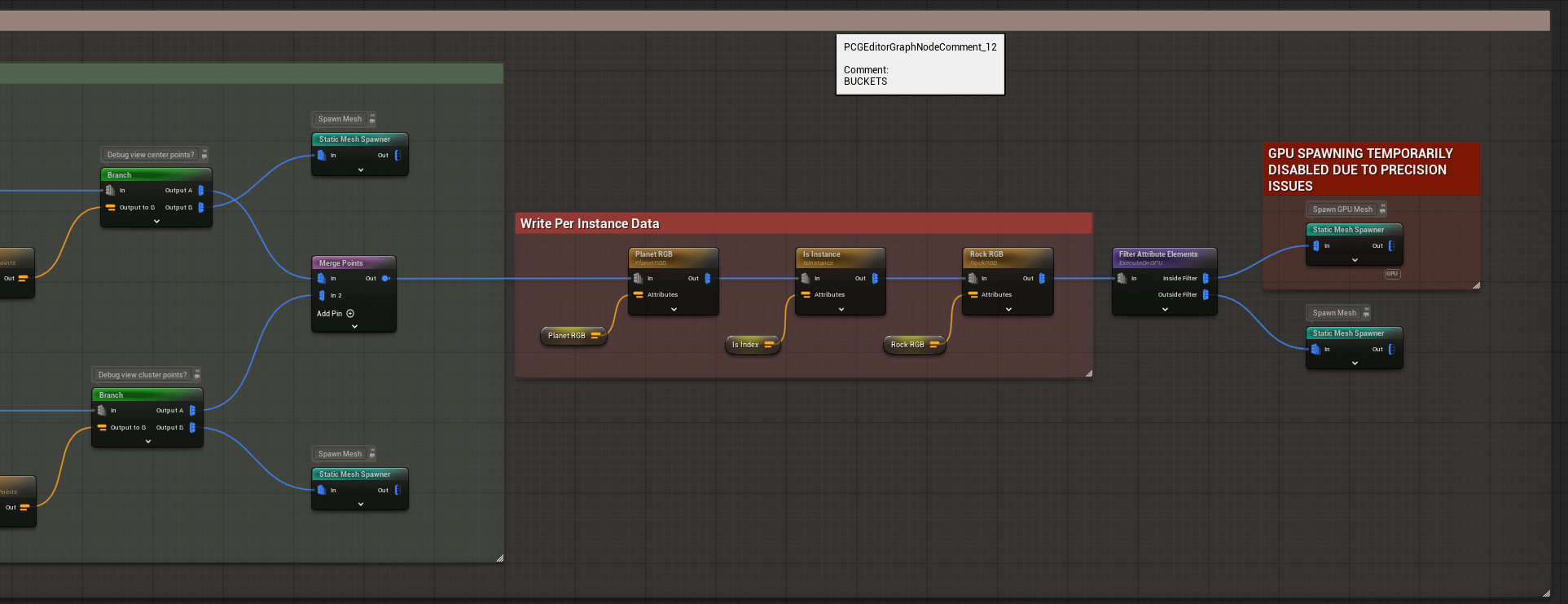

At the end of the graph, we assign per instance data (typically per-biome rock color and dirt color) and split points out to produce either GPU-based or non-GPU-based meshes. GPU-based meshes are typically more visual—i.e. small rocks and clusters that don’t require collision logic or as much overhead in the way of resources.

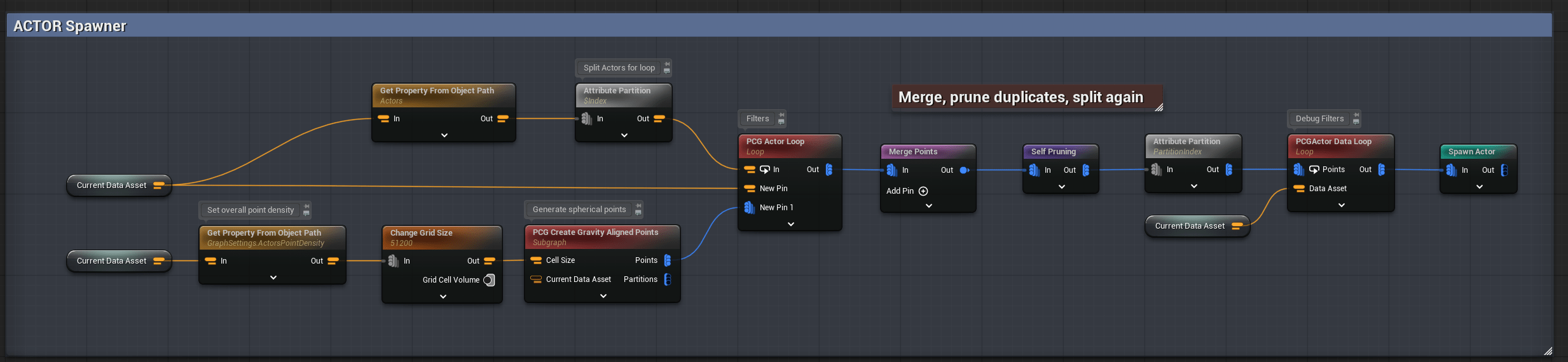

We use a similar sort of loop to spawn actors.

We can also spawn pre-generated level instances, typically consisting of assembled meshes (for large-scale cliffs, for instance).

The core function of the master graph is to run loops of logic based on the data assets it receives. This produces meshes and other actors which correspond to the points being generated. Normally you might assign actors and parameters within a graph itself, but our master graph reduces the need for additional graphs and per mesh guesswork by collecting and standardizing all of the relevant logic.

In Summation #

When all of this gets combined, our pipeline can handle creation and instantiation of modular data assets through PCG. In the data asset, we select the meshes and other actors we want, then control their distribution and cluster parameters. We run that through our PCG Master graph to handle gravity, point gen, and perform the sorts of logic needed before outputting to our surface. Using data assets in this way, we can quickly create sets of data to handle varying biomes on a planet-wide scale.